Attack Scenarios – How Adversaries Retrieve Sensitive Information

Alexandra KappAttack scenarios are used in privacy research to describe how an adversary potentially obtains sensitive information about a person. Such a scenario entails assumptions on side information available to an adversary, which sensitive information the adversary wants to retrieve, and how they use the side information to retrieve the sensitive information.

Such scenarios are used to evaluate the resilience of privacy measures against such attacks and help to prevent them. In the literature, there are many different kinds of attacks under various names. Thus, I hereby try to give an overview of the most common ones. In the context of mobility data, the adversary can have different objectives which can be summarized as:

- re-identification of a user (or de-anonymization): The “anonymous” records are linked to a user so that the adversary obtains all information about the user within the database.

- retrieve sensitive information: Retrieving sensitive information about a target, without necessarily re-identifying their records.

- learn anything additional about the user (not necessarily pre-defined sensitive information)

- retrieve the exact (current) location of a user: For example, in a location-based service app scenario, the adversary might know which data belongs to which user. But as the data is distorted, the objective is to identify the actual location from the perturbed data.

- membership of a user: Identify whether a particular user is part of the dataset (without necessarily uniquely identifying the data record of the target victim)

According to the objectives, there are respective attacks: re-identification attack, similarity attack, probabilistic attack, location inference attack and membership attack. This blog post provides a rough overview of those attacks. Note, that there are much more attack scenarios than the ones covered here, though usually they can be grouped into one of these relatively broad attack scenarios.

Re-identification Attack

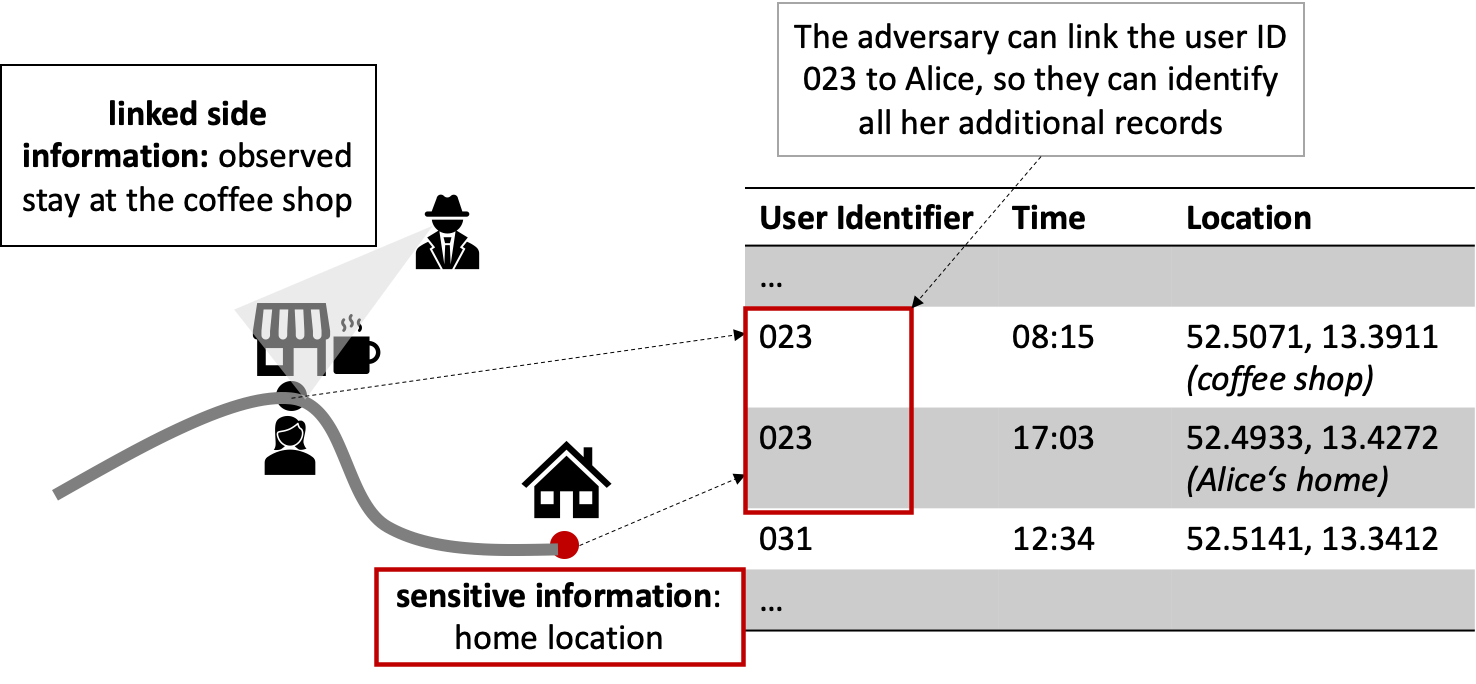

The re-identification (or de-anonymization) is one of the most commonly stated objectives. More specifically, re-identification is usually achieved with a record-linkage attack (Fung et. al, 2010): An adversary has access to some side information (e.g., an additional dataset, or a real-life observation) in addition to the anonymized dataset and links this information to the dataset so that re-identification of a person is possible. For example, as shown in Figure 1, an adversary knows that Alice visited a coffee shop at a certain time, and finds this record in the dataset, thus they can identify all other places Alice visited, revealing the sensitive home address.

Figure 1: Record-Linkage Attack

Figure 1: Record-Linkage Attack

Thus, there are two ways information can be critical to privacy:

- It can be the sensitive information itself, e.g., the home location (see this blog post on different ways mobility data can be sensitive).

- It can be used to re-identify a person in a dataset (linked side information) so that sensitive information can then be linked to the person.

This is the part where the adversary/privacy researcher can get creative: Which side information can be used how to successfully link individual records in the database?

Format of side information:

An adversary obtains information about a subset of spatio-temporal points, for example through a second data source or by observation (they see Alice in the coffee shop). If these spatio-temporal points make up a sub-trajectory of the trajectory within the anonymized database, they can be matched and Alice can be re-identified.

When the adversary knows important locations of Alice, such as her home or work location, they can often be used as quasi-identifiers and allow easy re-identification (Gambs et al., 2014) as location patterns of people are highly unique. One study (de Montjoye et al., 2013) showed that within the researched dataset only four spatio-temporal points were needed to uniquely identify a person. The most visited location during night times is usually the home location while the most visited location during working hours is the work location (assuming a setting with a full-time working person within an office). For example, Drakonis et al. (2019) showed that Twitter users could be de-identified based on their geotagged tweets.

Less obvious side information has also been used to de-anonymize individuals: Rossi et al. (2015) showed that mobility features such as speed or heading direction can be highly unique for individuals. Assuming, an adversary has access to such information about Alice (e.g., an app that “only” collects speed and compass information), they could use those mobility features to re-identify Alice within an anonymized dataset.

De Mulder et al. (2008) assume that the adversary has a location profile (Markovian model) of their target and uses the information about transition probabilities to re-identify them.

Scrivatsa and Hicks (2012) used a social graph as side information: a social network (e.g., Facebook) could be used to obtain information about friendships and create social graphs. As friends tend to have many overlaps in their physical encounters the authors used this information to link trajectories to social network IDs and thus re-identified up to 80% of the users correctly.

Similarity Attack

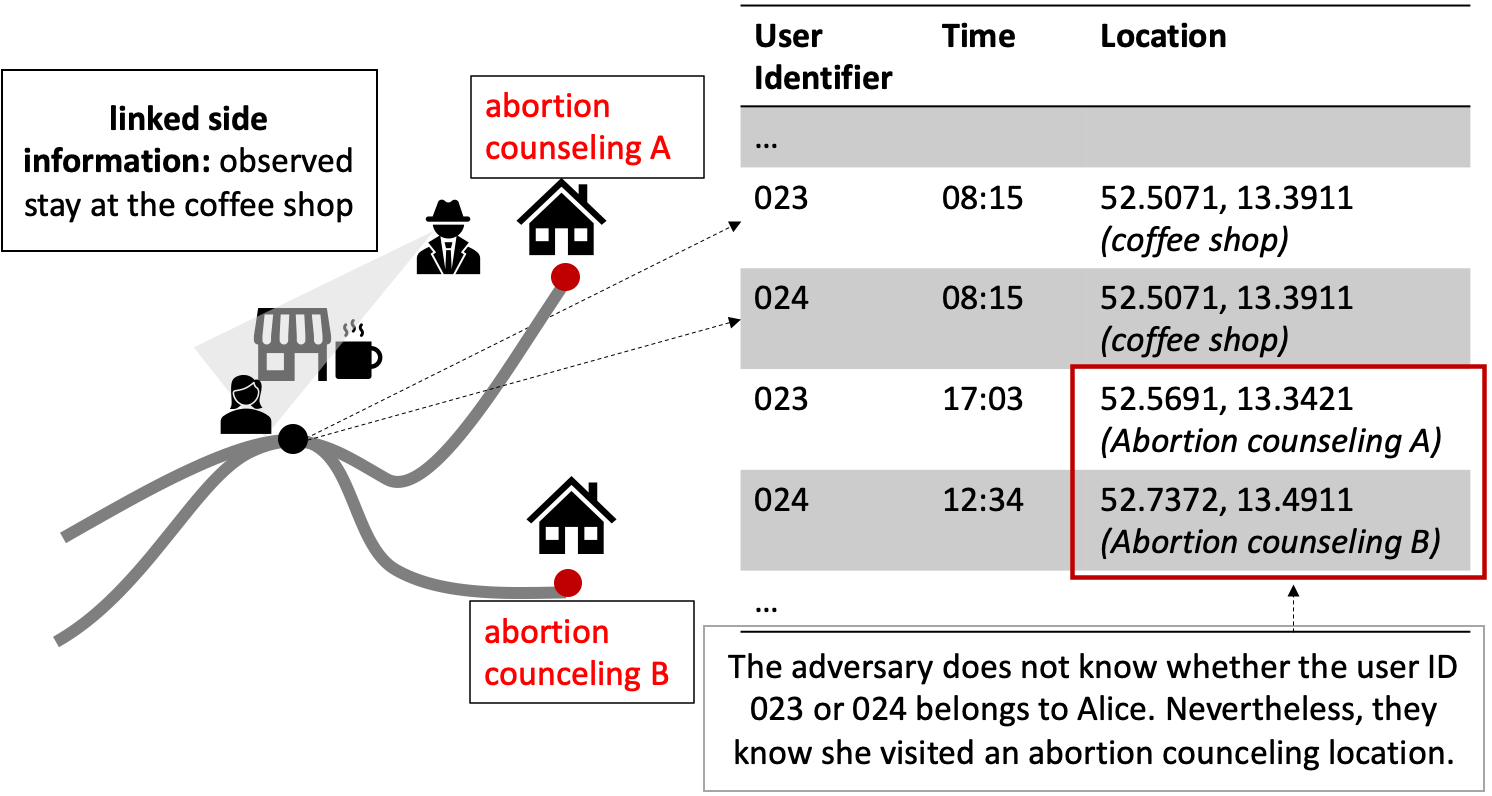

Unlike a re-identification attack, which is successful when a name can be put onto a single record, a similarity attack (or attribute-linkage attack) is already successful when sensitive information is retrieved (without identifying a user) (Fiore et al. 2019). For example, as shown in Figure 2, the adversary observes Alice at the coffee shop but there are two records in the database matching the time and place. Though, as both potential candidates visit an abortion counseling, the adversary knows that Alice must have been among those two, thus, obtaining sensitive information about Alice without having identified her in the database.

Figure 2: Similarity Attack

Figure 2: Similarity Attack

Localization Attack (Location Inference)

The setting for a localization attack (or location inference attack) is a little different: the adversary knows which information belongs to their target but the location information is perturbed by some anonymization technique (Li et al., 2022). Their objective is to infer the actual location of the user. This is often within the context of a (real-time) location-based service app.

For example, a restaurant recommendation app uses a privacy-preserving technique where not only the true user location is sent to the server but a set of multiple candidates, thus the actual user location is “hidden in the crowd”. The server retrieves the best restaurant recommendation for all candidates combined, which will be very likely also the best recommendation for the user.

An adversary could use information about the road network to remove all unlikely locations (i.e., those that are placed in inaccessible places, e.g., in a lake), thus increasing his probability of detecting the true user location (Xu et al., 2021) or use the semantics of places to identify the most probable true location (Tian et al., 2021).

Membership-inference attack

A membership-inference attack is successful if an adversary correctly identifies whether their target is a member of the dataset. Membership in a dataset might already be enough to reveal sensitive information (e.g., if someone is part of a database of a medical, religious, or dating app). As this is a dichotomous (yes or no) outcome the baseline for such attacks is commonly 50%, i.e., guessing by chance.

Pyrgelis et al. describe a membership-inference attack where a machine learning classifier is trained based on prior knowledge about the target’s membership in known aggregated datasets. This classifier is used to determine the membership of the user in the target dataset.

Probabilistic Attack

The probabilistic attack (or inference attack) is successful if anything additional is learned about a user by accessing the target database. Thus, the notion of a probabilistic attack is much broader than that of a similarity attack, as any information about a user is considered sensitive (Fiore et al. 2019).

Dieser Text erschien zuerst auf Alexandras privatem Blog.